Running a PDS for Your App: How OpenMeet Operates Its AT Protocol Integration

Every OpenMeet user gets an AT Protocol identity. Sign up with email or Google? We create a custodial account on our PDS. Already have a Bluesky handle? Bring it. Either way, events and RSVPs get published as AT Protocol records: portable, user-owned, and interoperable with the rest of the network.

We wanted this to be invisible to users. Nobody should have to understand DIDs or data servers to RSVP to a meetup. But behind that simplicity is real infrastructure: a PDS to operate, identities to manage, records to publish, and enough monitoring to sleep at night.

This is the story of how we built all of that. We happen to be on AWS/EKS, but the patterns work anywhere: another cloud, bare metal, a single VM.

Architecture Overview

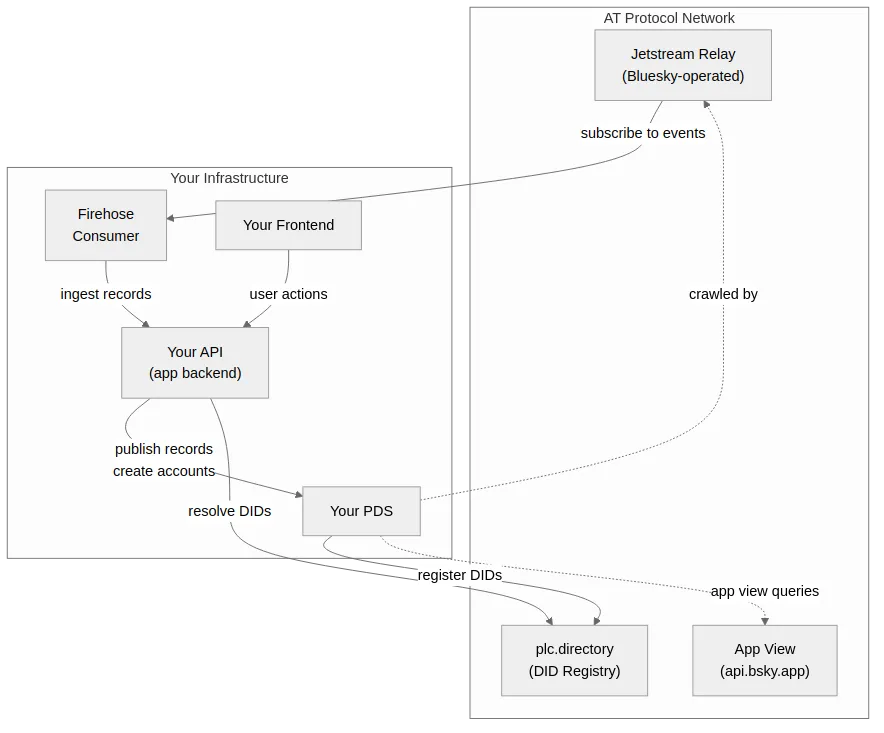

There are two data flows:

- Outbound: Our API publishes records to the PDS, which propagate to the AT Protocol network

- Inbound: A firehose consumer reads relevant records from the Bluesky relay back into our app

1. PDS Setup & Infrastructure

It starts with deploying the PDS itself. This was our first time operating one, so we kept the setup simple and invested early in things that would tell us when something was wrong.

The PDS Binary

We run the official Bluesky PDS (ghcr.io/bluesky-social/pds:0.4). It’s a Node.js application backed by SQLite: a single process handling XRPC endpoints, account management, repo storage, and blob storage. No fork, no patches, just the upstream image.

Key constraint: SQLite needs exclusive file access, which means single-replica only with no horizontal scaling and no rolling updates. On Kubernetes, we use a Recreate deployment strategy.

The Three-Container Pod Pattern

We run the PDS as a Kubernetes pod with three containers sharing one persistent volume:

| Container | What it does |

|---|---|

| pds | The PDS itself |

| backup | Automated SQLite backups to object storage on a cron |

| metrics-exporter | Custom Prometheus metrics |

All three mount the same PVC at /pds. The backup and metrics containers open SQLite in read-only mode, so they don’t interfere.

Not on Kubernetes? Same idea works with systemd services or cron jobs on a single VM.

Storage

The PDS keeps everything under one directory (/pds):

/pds/

├── account.sqlite # User accounts, repos, blobs metadata, invite codes

├── sequencer.sqlite # Event sequencing for firehose consumers

├── did_cache.sqlite # Cached DID document resolutions

└── actors/ # Blob storage (user-uploaded media)

A few things matter here:

- Use high-IOPS block storage (gp3, SSD). SQLite performance is I/O-bound.

- Pin the pod to the same availability zone as the volume. We use a

nodeAffinityrule hardcoded to the same AZ as our PVC. Without this, the pod can schedule in a different AZ where the volume can’t attach, and it just sits inContainerCreatingwith no helpful error message. We learned this the hard way. - Start with 5 GB. At roughly 5-10 MB per active user (repos + blobs), that supports 500-1000 users. We track

pds_db_size_bytesandpds_blobs_bytes_totalin Prometheus to see growth, andpds_accounts_totalto correlate with user count.

Networking & Handle Resolution

AT Protocol resolves user handles via DNS or HTTP. For handle resolution to work, two things are needed:

- A wildcard DNS record:

*.handledomain.compointing to the load balancer - Ingress/reverse proxy routing both

pds.handledomain.com(the PDS API) and*.handledomain.com(user handles) to the PDS

Without the wildcard, handle resolution fails and users can’t interact with the broader AT Protocol network. This one’s easy to miss.

Why We Use a Separate Handle Domain

Our app lives at openmeet.net. Our handles live at opnmt.me. They’re different domains on purpose, and if you’re setting this up, you’ll probably want to do the same.

Strictly speaking, the AT Protocol doesn’t require separate domains. You can use path-based routing to send /xrpc/*, /.well-known/atproto-did, and /oauth/* to the PDS while serving your app on other paths. But in practice, separate domains are cleaner. Here’s why we went that route:

Handle readability. The AT Protocol spec itself allows handles up to 253 characters (following DNS rules, with 63 characters per segment). But Bluesky’s hosted service enforces tighter limits (roughly 18 characters for the username segment), and other apps may follow similar conventions. A short handle domain like opnmt.me keeps handles like tom-scanlan.opnmt.me compact and readable regardless of where limits land.

SameSite cookie conflicts. When we initially tried running the PDS on the same domain as our app, we hit SameSite cookie errors that blocked OAuth flows. The PDS sets its own cookies, and when those share a domain with your app’s cookies, browsers can reject them under SameSite policies. A separate domain sidesteps this entirely.

Wildcard DNS conflicts. Handle resolution requires *.yourdomain.com routing to the PDS. If your app also uses subdomains on that domain (api.yourdomain.com, platform.yourdomain.com), you’ve got a routing conflict. A separate domain means the PDS gets clean wildcard ownership with no collisions.

Clean separation. App infrastructure on one domain, AT Protocol infrastructure on another. Different TLS certs, different DNS zones, different concerns. When something breaks, the blast radius is smaller.

The configuration reflects this split:

PDS_HOSTNAME=pds.opnmt.me # PDS API endpoint

PDS_SERVICE_HANDLE_DOMAINS=.opnmt.me # Handle suffix for users

The PDS itself lives at pds.opnmt.me, and user handles are *.opnmt.me. Your app’s API stays on its own domain entirely.

Key Configuration

# Identity: note the separate handle domain (see above)

PDS_HOSTNAME=pds.handles.example.com

PDS_SERVICE_HANDLE_DOMAINS=.handles.example.com

# ATProto Network: point at the public network for interoperability. Set these

PDS_DID_PLC_URL=https://plc.directory

PDS_BSKY_APP_VIEW_URL=https://api.bsky.app

PDS_CRAWLERS=https://bsky.network

# Access Control: require invite codes to prevent open registration

PDS_INVITE_REQUIRED=true

# Email: needed for account verification

PDS_EMAIL_SMTP_URL=smtps://USER:PASS@smtp.your-provider.com:465

PDS_EMAIL_FROM_ADDRESS=noreply@yourdomain.com

# Secrets: generate unique values per environment

PDS_ADMIN_PASSWORD=<random>

PDS_JWT_SECRET=<random-hex-64>

PDS_PLC_ROTATION_KEY_K256_PRIVATE_KEY_HEX=<random-hex-64>

PDS_CREDENTIAL_KEY_1=<random-base64-32-bytes>

These are all PDS configuration variables. They go into the PDS container’s environment, not your app. We manage them via Kustomize ConfigMaps and Secrets with different values per environment.

Important: PDS_PLC_ROTATION_KEY is the key that signs DID documents. It’s needed in every environment (dev and prod) since both create accounts with DID documents. Each environment should have a unique key. Lose it and there’s no way to update users’ DID documents. Back it up somewhere safe.

App-Side Configuration

Your app also needs configuration to talk to the PDS. These go into your API server’s environment, separate from the PDS itself:

# PDS connection: where your app sends requests

PDS_URL=https://pds.handles.example.com

PDS_ADMIN_PASSWORD=<same-as-pds> # For creating accounts, generating invite codes

PDS_INVITE_CODE=<from-createInviteCode> # Used when creating custodial accounts

# Handle generation

PDS_SERVICE_HANDLE_DOMAINS=.handles.example.com # So your app knows the handle suffix

# Credential encryption: for storing custodial passwords at rest

PDS_CREDENTIAL_KEY_1=<random-base64-32-bytes>

PDS_CREDENTIAL_KEY_2=<optional-rotation-key>

# OAuth: for users who bring their own AT Protocol identity

BLUESKY_CLIENT_ID=https://yourapp.com # Your OAuth client metadata URL

BLUESKY_REDIRECT_URI=https://yourapp.com/api/auth/bluesky/callback

BLUESKY_KEY_1=<pkcs8-private-key> # DPoP signing key(s)

The pattern: your app needs the PDS URL and admin password to create custodial accounts, encryption keys to store their credentials safely, and OAuth configuration to handle bring-your-own-identity users. These are your app’s secrets, not the PDS’s. The PDS doesn’t know about your credential encryption or OAuth keys.

Dev vs Prod Environments

| Aspect | Dev | Prod |

|---|---|---|

| DID Registry | Private PLC server (http://plc:2582 in-cluster) | Public plc.directory |

| Crawlers | Empty (PDS_CRAWLERS=): no broadcasting | https://bsky.network: full network participation |

In-cluster MailDev (smtp://maildev:1025) | Real provider (SES, SendGrid, etc.) | |

| Handle Domain | .dev.opnmt.me | .opnmt.me |

| PDS Hostname | pds.dev.opnmt.me | pds.opnmt.me |

| Dev Mode | PDS_DEV_MODE=true | false |

The key to dev isolation is two settings working together: private PLC and empty crawlers. The private PLC means DIDs created in dev don’t register in the public plc.directory. Empty PDS_CRAWLERS means the PDS doesn’t advertise itself to Bluesky’s relay network, so no records get indexed by the public AppView.

We run the PLC server using itaru2622/bluesky-did-method-plc:latest. It just needs a PostgreSQL database. It’s only deployed in dev; prod points directly at the public plc.directory.

Isolation isn’t automatic. Even with a private PLC and crawlers disabled, we hit a case where a record created in dev reached our production environment and triggered a real email notification. The exact leak path is still under investigation, but the lesson is clear: environment isolation isn’t complete just because PLC and crawlers are separated. Firehose consumers and downstream processors need environment-aware filtering too.

2. Linking Users to AT Protocol Identities

With the PDS running, the next question is: how do existing app users connect to it? We already had users with email and Google accounts. We needed to give each of them an AT Protocol identity without disrupting their experience.

The Identity Table

We added a single table (userAtprotoIdentities) that bridges our existing user model to the AT Protocol world:

CREATE TABLE "userAtprotoIdentities" (

"id" SERIAL PRIMARY KEY,

"userUlid" CHAR(26) NOT NULL UNIQUE, -- FK to our users table

"did" VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL UNIQUE, -- did:plc:xxxx

"handle" VARCHAR(255), -- alice.opnmt.me

"pdsUrl" VARCHAR(255) NOT NULL, -- https://pds.opnmt.me

"pdsCredentials" TEXT, -- encrypted password (custodial only)

"isCustodial" BOOLEAN DEFAULT true,

"createdAt" TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW(),

"updatedAt" TIMESTAMP DEFAULT NOW()

);

That’s it. One row per user. The userUlid points to our existing users table, the did is their AT Protocol identity. Everything else is operational metadata.

The key design decisions:

- One identity per user. The unique constraint on

userUlidenforces this. We thought about supporting multiple identities per user, but the complexity wasn’t worth it. Users think of themselves as one person. - DID is the real identity, not the handle. Handles can change (alice.bsky.social → alice.custom.com). The DID is permanent. We index on both, but the DID is what matters.

- Custodial vs. bring-your-own. The

isCustodialflag andpdsCredentialscolumn handle both cases. Custodial users have encrypted credentials we manage. OAuth users don’t; we just store the DID and PDS URL. - Encrypted credentials, not plaintext. The

pdsCredentialscolumn stores AES-256-GCM encrypted JSON containing the custodial password. We support key rotation by versioning the encryption keys. For OAuth users, this column is null; their sessions are managed separately (see Session Management below).

A note on session token storage. For OAuth users, we store session state (including refresh tokens) in Redis. This is necessary because we need to act on behalf of users to publish events and RSVPs, and in some cases, other group members may need to edit records owned by a user’s DID. Today, AT Protocol doesn’t have a built-in delegation model for group permissions, so we hold onto session tokens to perform these operations. This is a pragmatic tradeoff: it works, but it means we’re custodians of active session material. We’d prefer a protocol-level solution for delegated writes, and expect this area to evolve. If you’re building something similar, consider how long you retain tokens and what happens when they expire.

How Users Get Identities

There are two paths, and they converge on the same table:

Path 1: We create it for them (custodial)

Most users sign up with email or Google. They don’t know what AT Protocol is, and they don’t need to. Behind the scenes:

- User signs up → we generate a handle like

userslug.opnmt.me - We create a PDS account with a random 32-byte password

- We encrypt the password and store it alongside the DID

- The user now has an AT Protocol identity without lifting a finger

They can publish events to the protocol, RSVP to things, all without ever thinking about DIDs or PDS servers. Later, if they want to take ownership of that identity, they can. After taking ownership, users may login using their atproto identity or their original auth method.

Path 2: They bring their own (OAuth)

Users who already have a Bluesky handle (or any AT Protocol identity) log in via OAuth. We store their DID and PDS URL, but pdsCredentials stays null and isCustodial is false. We don’t store their password. Instead, the OAuth session (including refresh tokens) lives in Redis, managed by @atproto/oauth-client-node. This lets us act on their behalf within the scopes they granted during the OAuth flow.

Account Linking

Here’s the tricky case: someone signs up with Google, gets a custodial identity, then later wants to use their existing Bluesky handle instead.

The flow:

- From an authenticated session, user enters their AT Protocol handle

- OAuth authenticates them on their PDS

- We verify the identity and update the link

- Future ATProto logins resolve to the same account

We intentionally don’t auto-link by email. The emailConfirmed field comes from the user’s PDS via com.atproto.server.getSession(), and a malicious PDS operator could return emailConfirmed: true for any email address. We do read this field (it affects account activation status), but we never use it to match accounts. The only safe path is user-initiated linking from an already-authenticated session.

Session Management

Identity links tell us who a user is on the protocol. Sessions let us act on their behalf. The two user types need different session strategies:

- Custodial users: Decrypt the stored password, call

com.atproto.server.createSession, and cache the resulting JWT in Redis. Since we have the password stored, we can always re-authenticate if the session expires. In hindsight, our current 15-minute cache TTL is overly conservative. We could cache for the full JWT lifetime (the way we do for OAuth sessions) and only re-authenticate when the token actually expires. The PDS is local so re-auth is cheap, but there’s no reason to do it more often than necessary. - OAuth users: Use

@atproto/oauth-client-nodewith DPoP-bound tokens. DPoP (Demonstrating Proof of Possession) cryptographically binds access tokens to a specific client by requiring proof of a private key with each request. This is mandatory in AT Protocol’s OAuth; it means a stolen token is useless without the corresponding private key. The OAuth client handles token refresh automatically; sessions are stored in Redis with no TTL, relying on AT Protocol’s native token expiry.

We built a unified PdsSessionService that returns an authenticated AtpAgent regardless of which type of user it is. The rest of the codebase calls getSessionForUser() and gets back an agent; it doesn’t need to know whether the user is custodial or OAuth. The tradeoff is that OAuth session failures surface at publish time rather than at login time, which can be confusing for users whose tokens have expired.

3. Publishing Records

Now users have identities. The next step is putting their data on the protocol.

We use community-standard lexicons from lexicon-community:

community.lexicon.calendar.event: event recordscommunity.lexicon.calendar.rsvp: attendance records

These are the same schemas that smokesignal.events and dandelion.events use. Events created on any of these platforms show up on all of them, with zero coordination between the projects. This is the part of AT Protocol that gets us excited.

Our publishing model is PDS-first: write to AT Protocol, get back the URI and CID, then store those references in PostgreSQL. The PDS is the source of truth for published records. Our database is a query index.

Create/update event in the app

→ Save event to PostgreSQL

→ Get authenticated session for user

→ createRecord / putRecord on the PDS

→ Save atprotoUri, atprotoRkey, atprotoSyncedAt back to the event

If the PDS write fails, the event still gets saved to the database so users don’t lose their work. The atprotoUri stays null, and on the next edit, a needsRepublish() check detects the missing URI and retries the publish. No background queues or complex retry buffers. Simple, and the eventual consistency resolves itself naturally through user activity.

4. Monitoring

Publishing records and managing identities is the happy path. But we’re running a service that holds user data and signs DID documents. If it goes down or behaves strangely, we need to know before our users do.

The Node.js PDS doesn’t expose Prometheus metrics natively. So we built a sidecar that queries the SQLite databases directly in read-only mode.

What we track:

| Metric | Why it matters |

|---|---|

pds_up | Is the PDS health endpoint responding? |

pds_accounts_total | Growth tracking |

pds_accounts_by_status{status} | Active vs deactivated |

pds_blobs_total / pds_blobs_bytes_total | Storage growth |

pds_sequencer_position | Event stream progress (stalled = problem) |

pds_invite_codes_total{status} | Available / exhausted codes |

pds_db_size_bytes{database} | Per-database storage |

pds_health_check_duration_seconds | Latency histogram |

The exporter uses better-sqlite3 (Node.js) to query the SQLite files every 15 seconds, exposed on :9090/metrics.

Our Alert Rules

These live in our Prometheus ConfigMap alongside other application alerts:

# PDS is down: most critical

- alert: PDSDown

expr: pds_up == 0

for: 2m

severity: critical

# Storage approaching capacity: gives time to resize

- alert: PDSVolumeNearFull

expr: |

kubelet_volume_stats_used_bytes{persistentvolumeclaim="pds-data"}

/ kubelet_volume_stats_capacity_bytes{persistentvolumeclaim="pds-data"}

> 0.8

for: 10m

severity: warning

# Storage critical: act now

- alert: PDSVolumeAlmostFull

expr: |

kubelet_volume_stats_used_bytes{persistentvolumeclaim="pds-data"}

/ kubelet_volume_stats_capacity_bytes{persistentvolumeclaim="pds-data"}

> 0.95

for: 5m

severity: critical

# Health checks getting slow: early warning

- alert: PDSHealthCheckSlow

expr: histogram_quantile(0.95, sum(rate(pds_health_check_duration_seconds_bucket[5m])) by (le)) > 1

for: 5m

severity: warning

# Metrics exporter having problems: may indicate SQLite issues

- alert: PDSScrapeErrors

expr: increase(pds_scrape_errors_total[1h]) > 10

for: 5m

severity: warning

We also track invite code availability, since running out silently breaks account creation:

# Invite codes getting low: generate more soon

- alert: PDSInviteCodesLow

expr: pds_invite_codes_total{status="available"} < 100

for: 5m

severity: warning

# Invite codes almost gone: account creation will fail

- alert: PDSInviteCodesCritical

expr: pds_invite_codes_total{status="available"} < 25

for: 5m

severity: critical

External Health Checks

We also configure external HTTP probes against /xrpc/_health. The load balancer health check targets this endpoint too. External probes catch things internal checks miss: DNS problems, certificate expiry, ingress misconfiguration.

5. Backup & Recovery

Monitoring tells us when something is wrong. Backups let us recover when something goes very wrong. Since the PDS holds user identity data and signed records, losing it would mean losing the ability to update users’ DID documents and their published content. We take this seriously.

The backup sidecar runs every 6 hours:

# For each SQLite database: hot backup (consistent snapshot while PDS runs)

sqlite3 /pds/account.sqlite ".backup /tmp/account.sqlite"

gzip /tmp/account.sqlite

# Upload to object storage (S3, GCS, R2, MinIO, etc.)

# For blob storage: tar and upload

tar -czf /tmp/actors.tar.gz -C /pds actors

# Upload to object storage

The key insight: sqlite3 .backup creates a consistent snapshot of a running database without stopping the PDS. Safe for hot backups.

We organize backups by environment and timestamp:

s3://your-backups/pds/{environment}/pds-account_2026-02-09_06-00-00.sqlite.gz

s3://your-backups/pds/{environment}/pds-actors_2026-02-09_06-00-00.tar.gz

We use IAM role mechanisms rather than storing credentials in the pod.

Restore Procedure

- Scale down the PDS (replicas → 0)

- If using GitOps (ArgoCD, Flux), pause auto-sync

- Mount the PVC to a temporary pod

- Download and extract backups from object storage

- If restoring into a different environment, transform domains in the SQLite databases and update the

pdsUrlcolumn in your app’suserAtprotoIdentitiestable to reference the new PDS domain - Scale PDS back up

- Re-enable GitOps sync

Cross-environment restore, for testing restores, requires rewriting handles and domains in the SQLite data. We have a script for this, but it’s untested and may itself be a source of issues. This is an area where we need more practice before relying on it in a real recovery scenario.

6. Operational Runbook

The sections above cover how things are built. This section covers what we actually do day-to-day to keep it running.

Generating Invite Codes

We use invite codes to prevent open registration on our PDS. When our API creates a custodial account, it consumes one use from a high-count invite code generated like this:

curl -s -u "admin:$PDS_ADMIN_PASSWORD" \

"https://pds.yourdomain.com/xrpc/com.atproto.server.createInviteCode" \

-X POST -H "Content-Type: application/json" \

-d '{"useCount": 100000}'

We store the returned code in our app’s configuration. Monitoring pds_invite_codes_total{status="available"} prevents running out silently.

Environment Reset (Dev)

When we need a clean dev environment:

- Scale down PDS and PLC

- Delete the PDS PVC (volume deletes with it)

- Drop and recreate the PLC database schema

- Reset the application database (migrations + seeds)

- Recreate the PVC, scale everything back up

- Generate a fresh invite code

Gotcha: After deleting the PVC, it must be recreated before the PDS pod can start. Kubernetes won’t auto-create a PVC from a deployment spec.

PLC Directory Pitfalls

Switching a dev PDS between private and public PLC causes problems. Accounts created under one won’t resolve under the other. The DIDs exist in one registry but not the other.

Options:

- Migrate DIDs using the goat CLI to export/import PLC operations

- Delete and recreate affected accounts

- Pick one PLC strategy per environment and stick with it

SMTP Gotcha

The PDS is configured to send email verification during account creation. If email silently fails, accounts get created with emailConfirmedAt: null, which can cause issues downstream.

Common mistake: Using smtp:// when the provider requires smtps:// (TLS on connect, typically port 465). The PDS won’t error on misconfigured SMTP; it just silently fails to send.

Test email delivery after any SMTP configuration change.

7. Looking Back

We’ve covered the infrastructure, the identity model, the publishing flow, and the operational work. Here’s the honest summary of what we got right, what surprised us, and what we’d tell someone starting this today.

What Worked

- Community lexicons were the best decision we made. Using shared schemas (

community.lexicon.calendar.*) means our events federate with smokesignal.events without any coordination between the two projects. That’s the promise of AT Protocol, and it actually delivers. - Custodial-first, sovereign-later is the right UX tradeoff. Most users don’t care about self-hosting on day one. Giving them an AT Protocol identity behind the scenes, with the option to take ownership later, gets them on the protocol without friction.

- One identity table bridging our user model to AT Protocol was the right level of abstraction. We considered more complex schemas and are glad we didn’t go there.

- PDS-first publishing kept the architecture simple. No sync queues, no eventual consistency headaches. Write to PDS, save the reference, done.

- The three-container pod (PDS + backup + metrics) kept concerns separated while sharing storage. Each component updates independently.

What Bit Us

Most of these are covered in the sections above, but collected here for easy scanning:

- AZ pinning. The PDS pod scheduled in a different AZ from its volume. It hung in

ContainerCreatingwith no useful error. Now we pin it withnodeAffinity. - SMTP misconfiguration. The PDS silently swallows email failures, as far as we can tell. It’s worth verifying an email can go out.

- Invite code exhaustion. Ran out, couldn’t create accounts. Now we have Prometheus alerts at 100 and 25 remaining.

- PLC environment mismatch. Switching between private and public PLC caused DID resolution failures.

- Dev-to-prod leak. A record created in dev reached prod and triggered a real notification. Still investigating. Environment isolation needs more than PLC and crawler settings alone.

- SQLite scaling ceiling. Fine for now, but single-replica-only has a finite capacity. The limit is rumored to be around 10k repos per PDS.

What’s Missing

- Metrics from the PDS. Our metrics exporter covers the basics, but it could be a standalone project. We have a start and would welcome contributors.

- Delegated account management. We currently hold OAuth session tokens to publish on behalf of users, and manage custodial credentials ourselves. Tranquil PDS offers account delegation with permission levels and audit logging, and has been exploring social provider login (Google, Apple, etc.) as well. We plan to evaluate it in March.

- Automated backup restore testing. We back up every 6 hours and have restored individual backups manually, but the restore process isn’t automated. Tools like PDS MOOver now support repo-level backup and restore, which we haven’t explored yet.

- Custodial credential key rotation. We built the schema for key rotation (

PDS_CREDENTIAL_KEY_2), but haven’t built the actual rotation procedure. Credentials encrypted with the old key need to be re-encrypted on access. - Protocol-level group permissions. AT Protocol doesn’t have a delegation model for group writes. When a group admin edits an event owned by another member’s DID, we use stored session tokens. We’d prefer a protocol-native solution.

- Turnkey dev environment isolation. Testing PDS integration in isolation is difficult. Standing up a private PLC, PDS, and the right crawler settings for a clean dev environment takes manual work. A ready-made solution for this would help anyone building on AT Protocol.

Resources

- Bluesky PDS: Official PDS image and documentation

- AT Protocol Specification: Protocol documentation

- Lexicon Community: Community-standard schemas for calendar, location, and more

- did-method-plc: PLC directory server (for dev environments)

- goat CLI: AT Protocol Swiss Army knife (DID operations, repo inspection)

- OpenMeet: Our application

- Your Identity, Your Events: How we explain AT Protocol identity to users

This reflects our setup as of February 2026. We’re still early in this, still learning, and the AT Protocol ecosystem moves fast. If something here looks wrong or outdated, it probably changed after we published. Check the official docs, and if you’re building something similar, we’d love to hear about it.